Am I My Brother’s Keeper? The Future of the Episcopal Church in Central Florida

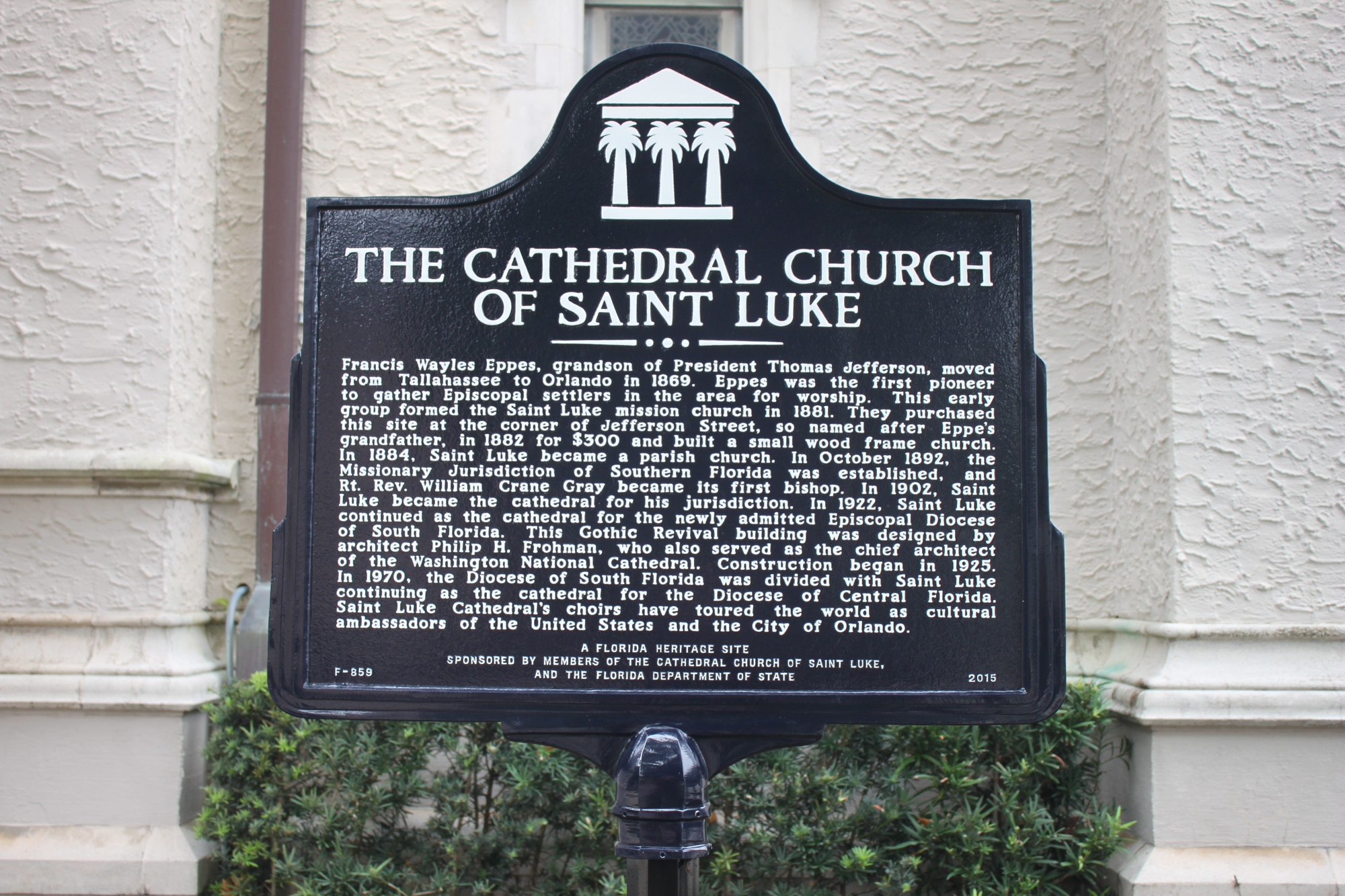

The Cathedral Church of Saint Luke in Orlando is a stunning Gothic Revival church with a rich cultural heritage in pioneering Florida.

Over Easter, I attended vigil at the Cathedral Church of Saint Luke in Orlando. The stunning Gothic Revival church founded by Thomas Jefferson’s grandson has a rich cultural heritage in pioneering Florida. Today, it is among the last conservative holdouts in a denomination many consider a lost cause.

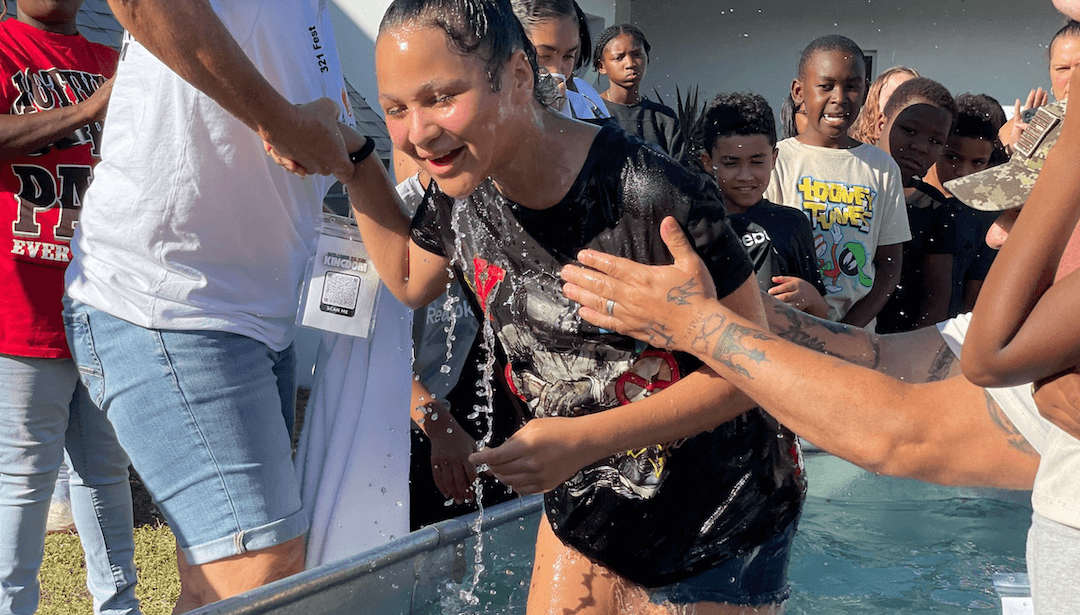

The Easter vigil is a traditional service in Christian practice held on Holy Saturday in anticipation of the resurrection of Christ on Sunday morning. It is the culmination of the Paschal Triduum services, including Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, which follow the last moments of Christ’s betrayal, death, and resurrection and capstones the Lenten season.

In the video I’ve included, you can hear the moment the vigil “passes.” The crowd rings bells and the organ launches into festive music, celebrating the resurrection of Christ. (Other scenes depicted include the lighting of the Paschal Candle, left, and a Holy Week service in the adjoining chapel, right).

Following the Resurrection celebration, the Rev. Jonathan Turtle, rector of Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Audubon Park, delivered the evening’s sermon. “Jesus Christ really did live and die before being raised from the dead…” he said. “That’s the hope of Easter—that something can happen in this life to make you a truly new person.”

Saint Luke’s is the Cathedral Church for the diocese of Central Florida and is the see (or “seat”) of Central Florida’s Episcopal Bishop, Justin S. Holcomb. Bishop Holcomb presides over 15 counties in Central Florida, including Brevard.

The now-Cathedral was built as a mission church in 1881 thanks to the effort of Wayles Eppes—the grandson of Thomas Jefferson. “They purchased this site at the corner of Jefferson Street, so named after Eppes’ grandfather, in 1882 for $300 and built a small wood frame church” the historical marker outside the church reads.

The current cathedral sits on the same property and dates to 1925. It was designed by Phillip H. Frohman, who was also the architect of the National Cathedral in Washington. In the photos, you can get a taste of the ornate wood, stone, and glass work throughout the sanctuary.

The Episcopal Church, a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion, has a long heritage in the United States, and much of Central Florida and Brevard’s early Christian history finds roots in Episcopal worship. Over half of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were Episcopalians along with the nation’s first President, George Washington.

The oldest standing building in Brevard County, the Sam’s House cabin in Merritt Island, was used for Episcopal worship. Additionally, several of Brevard’s oldest congregations, including Holy Trinity in Melbourne, Saint Gabriel’s in Titusville, Saint Mark’s in Cocoa, and St. Luke’s in Titusville (all founded between 1886-1888), are Episcopalian.

But today, the Episcopal Church is largely considered a liberal denomination after a long slide in orthodoxy that has been mirrored across mainline denominations. The Church’s liberalization has resulted in its fracturing, with break-off denominations forming that hold to varying degrees of conservative doctrine. These splinter churches often brand themselves as Anglican, a term that refers to churches that find heritage in the tradition of the Church of England, to differentiate themselves from the Episcopal Church. Several of these “continuing Anglican” churches are represented in Brevard, including Good Shepherd in Palm Bay, Saint Paul’s in Suntree, Prince of Peace in Viera, Glory of God in Cocoa, and St. Patrick’s in Port St. John.

Most recently, in 2018, the Episcopal Church mandated the availability of same-sex marriage rites church-wide under Resolution B012. Prior to the resolution, the canons of The Episcopal Church allowed local bishops to make their own policy within the bounds of their diocese.

As a conciliatory move, the resolution did provide a compromise for conservative Bishops who cannot in good conscience authorize same-sex marriage rites, allowing them to defer oversight of any requested marriages to another bishop outside of the diocese.

Central Florida, then under Bishop Gregory Brewer, was one of only eight out of 111 dioceses that opposed Resolution B012. Today, under Bishop Holcomb, it is one of just six that continue to uphold a conservative stance on marriage, restricting rites to the traditional union of one man and one woman (the other five conservative dioceses at the time of writing are Dallas, Tennessee, Springfield, the Virgin Islands, and the Diocese of Florida, based in Jacksonville).

The Episcopal Church in Central Florida represents 23,000 Christians worshipping in 81 congregations across 15 counties—all, save one (Saint Richard’s in Winter Park requested same-sex marriage rites under the compromise in 2018 and was referred to Bishop Terry White of Kentucky), adhering to a traditional, conservative marriage doctrine against the pressure of a near-overwhelming liberal consensus within the historic church body.

For conservative Christians outside of the Episcopal Church, these happenings may seem inconsequential. Out of sight is out of mind, and closer congregational needs and denominational battles take precedence. Greater still, historic theological differences may cause some to reason that The Episcopal Church deserves to fall.

Perhaps that is true, but the loss of the Episcopal Church in Central Florida would deal a significant blow to Christian faith formation in a diocese that sits at the epicenter of the space industry. That loss would affect not only what is taught from the pulpit, but also what is taught to children in the diocese’s 17 schools—children who will grow to see humanity take to the stars and be recruited by the companies sending it there as the industries of the future continue to plant roots on our shores.

Are these young minds something we can afford to lose?

“And the Lord said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: Am I my brother's keeper?”

— Genesis 4